Dynamic Page Assembly using Service Workers

by Catalin Dumitru

There’s a lot of buzz surrounding Service Workers recently, and rightfully so. They allow background processing, push notifications, offline applications, and most importantly, intercepting network requests and returning cached resourced. The former will have the biggest impact on page load times, and is the basis for this Blog post.

We will leverage offline caches and network intercepts to dynamically alter regular HTTP pages using Service Workers. The server will send just a skeleton of a page which will get expanded by our Service Worker. We will inject cached portions of the final HTML page (called “partials” in our case) into predefined placeholders stored inside the requested page.

By doing so, you can cache portions of your web page which change very rarely or which repeat on multiple pages (such as the header or footer) and just deliver the dynamic content which cannot be cached. In practice, this doesn’t have a huge performance gain as we’ll see at the end of the article, but it might have it’s uses in the real world.

But talk is cheap, so let’s get to the code.

Prerequisites

This is not a tutorial for Service Workers, so I’m assuming you already know how to install, update and debug Service Workers. We will also use the newly released Fetch api to intercept Network requests, and IndexDB for cache storage. To get up to speed, here are some very well written articles:

Structure

To start off, here are the files we’ll be working with (you can get the complete example from the github repo)

index.html

partials/

footer.html

header.html

page1.html

page2.html

page3.html

serviceworker.jsAnd to better understand what we’re trying to do, here is the HTML content of the two pages the user will request explicitly:

index.html

<html>

<head>

<!-- Some script we'll see in a moment -->

</head>

<body>

<ul>

<li><a href="partials/page1.html">Page 1</a></li>

<li><a href="partials/page2.html">Page 2</a></li>

<li><a href="partials/page3.html">Page 3</a></li>

</ul>

</body>

</html>partials/page1.html

{{/partials/header.html}}

<div style="padding: 20px;">

Howdy from page 1 <b>#time</b>

</div>

{{/partials/footer.html}}Now you’ve probably guessed what the end result will be. The index page is just a regular HTML page with three links, but the three pages contain two special tags, which signals to the background service worker to inject some arbitrary content (the “header.html” and “footer.html” pages) before presenting the HTML content to the user.

The service worker will fetch the content of a predefined list of “partials” which can be injected inside our three pages, namely the header and footer. We will store the content of these two partials inside IndexDB, so the content can be reused between multiple page requests.

Finally, lets look at the header and footer content, to see what will get stored and injected into our main pages.

partials/header.html

<div style="padding: 20px; background-color: #6ad1f0;">

This is the header: <b>#time</b>

</div>partials/footer.html

<div style="padding: 20px; background-color: #e6e6e6;">

This is the footer: <b>#time</b>

</div>Nothing fancy, but it is important to note that the #time field will

get replaced at runtime with the timestamp of when the browser fetched

the specific partial. This way, we can track which pages are requested, and which

are cached.

Now, let’s get to some JavaScript

Setting Up

At this stage, we’ve define our static pages, so it’s time to make them dynamic. But before we go any further, I’d like to point out that none of the code written below is production ready. I’ve kept the code to a bare minimum to be easy to understand, but it is in no way robust.

With that taken care of, let’s start off by installing our service worker:

navigator.serviceWorker.register("/partials/serviceworker.js", { scope: "/partials/" })

.then(

function(registration) {

console.log("Service worker installed successfully!", registration);

},

function(err) {

console.error("Error while installing service worker: ", err);

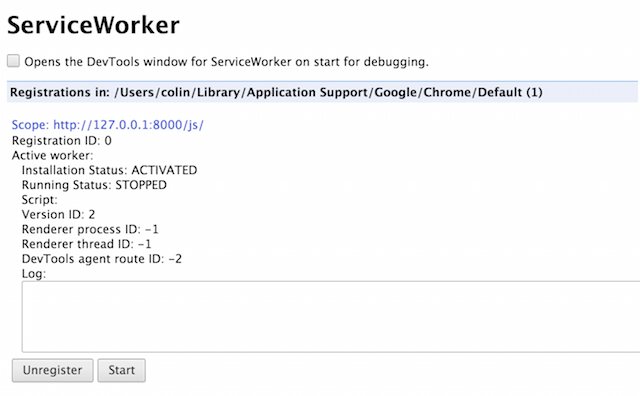

});Our service worker is registered under the “/partials/” scope; this way it can

intercept all requests to that specific folder. This particular snippet

is injected inside the index.html file. You can verify that everything is

working correctly by going to the chrome://serviceworker-internals/ page inside Chrome,

where you should see something similar to this:

Your worker should be in the Active state. And as a warning, updating service

workers is a bit of a pain, and I haven’t found a reliable way of doing so.

My development processes usually involves editing the JS from the Inspect

window in Chrome.

Now let’s get indexing with some IndexDB.

We’re using a storage system for our service workers because their state is not persistent. The logic for starting and stopping Service Workers is controlled entirely by the browser, so if you want state to persist between multiple resets, you’ll need to use a storage system, such as local storage, IndexDB or the upcoming Cache api.

It’s not easy to use, but it provides much more storage space than local storage (5 MB per origin in Google Chrome, Mozilla Firefox, and Opera; 10 MB per storage area in Internet Explorer). So let’s get to some setup code:

/* These three partials will be cached by our service workers and injected into our main pages */

var templates = [

"/partials/header.html",

"/partials/footer.html"

],

indexDBRequest = indexedDB.open("TemplatesDatabase", 9),

/* Once it resolves, we will use this promise to store and retrieve partials from IndexDB */

db = new Promise(function (resolve, reject) {

indexDBRequest.onupgradeneeded = function (event) {

var db = event.target.result;

/* Create an object store to hold the content of our partials */

templateStore = db.createObjectStore("templates", {

keyPath: "path"

});

/* Also create an index on the partial path, to query over it later */

templateStore.createIndex("path", "path", {

unique: true

});

templateStore.transaction.oncomplete = function (event) {

resolve(db);

}

};

indexDBRequest.onsuccess = function (event) {

resolve(event.target.result);

};

});Nothing revolutionary, we just initialise IndexDB and create the

templates object store which will contain the HTML content of our cached

partials. And because the IndexDB Api is mostly async, we’ll be using

Promises to ensure everything is setup before we start storing objects.

Storing Partials into IndexDB

Now that we have a basis for storing partials, it’s time to do just that. We’ll start off by defining an auxiliary method for storing a partial path (e.g. ``/partial/header.html`) and it’s correspondent content.

function storeTemplate(template, body) {

return new Promise(function (resolve, reject) {

db.then(function (db) {

/* Create a new transaction for storing a partial path and it's content */

var store = db.transaction("templates", "readwrite").objectStore("templates");

/* Add the actual partial */

store.add({

path: template,

body: body.replace(/#time/, new Date().toString())

});

});

});

}We open a new transaction to IndexDB on the “templates” store, and then save our content into said store. As was mentioned above, most IndexDB operations are Async, so we’ll once again be using Promises to tie all calls.

We are also replacing the #time field defined inside our partial content with the

timestamp when the request was made. This way, we can validate that the HTML

content which is injected into our files is requested only once.

Now it’s time to fetch the partial content. We will be doing so during the “install” phase of our service worker, so we can delay the process until all partials have finished downloading and are stored inside our DB.

this.addEventListener("install", function (e) {

e.waitUntil(

templates.map(function (template) {

return fetch(template)

.then(function (res) {

/* The text() method returns a Promise, which we chain */

return res.text();

})

.then(function (res) {

/* The storeTemplate() method also returns a promise */

return storeTemplate(template, res);

});

})

);

});The install event, which we’re using in our sample code, is fired once the

browser finishes fetching the JS of our service worker and is ready to be

activated. Normally, the install process of the worker is finished as soon

as the the handler defined above is finished, but we can delay the activation

process until the promises sent to the e.waitUntil(...) method are resolved.

This way, if the partials have not finished caching, the server can still

send the full HTML of the requested pages, so the user experience will be

unchanged. You can signal to the server that the partials have not finished

downloading by adding additional headers to the fetch(...) call we’ll define

below.

Each of our partials are mapped to a promise which will get resolved once the HTML content is fully downloaded and stored into IndexDB. So after the install process is finished, we will have the full offline version of our header and footer HTML pages, which we can inject into our three pages.

Intercepting requests and performing dynamic assembly

We’re finally to the most interesting part, the actual page assembly. Well… not quite. We still have to define an auxiliary method for retrieving our cached partials from IndexDB:

function getTemplate(template) {

return new Promise(function (resolve, reject) {

db.then(function (db) {

var store = db.transaction("templates").objectStore("templates"),

request = store.get(template);

request.onerror = reject;

request.onsuccess = function (event) {

if (request.result) {

resolve(request.result);

} else {

reject();

}

}

});

});

}There’s not much to say for this method, it’s just standard IndexDB code for retrieving objects stored into an object store.

Now for the good part, intercepting requests. With the new Service Worker API,

you can define a handler on the fetch event which will intercept all network

requests on the scope path we defined inside our initialisation stage

(“/partials/”). This is where our three pages live. So let’s see the beast:

this.addEventListener("fetch", function(event) {

var mainPromise = fetch(event.request.url)

.then(function(request) {

/* The text() method will return a Promise which resolves to the full

text content of the requested page -- the page HTML */

return request.text();

})

.then(function(text) {

/* With the full HTML of the page, we can now scan the content for partials,

which are of the form {{<partial url>}} */

return Promise.all(

[

/* Also add the initial page content, so we can replace the placeholders

with the full HTML of the partials */

new Promise(function(resolve) {

resolve(text);

})

].concat(

/* For each placeholder, fetch the HTML from IndexDB and return it

as a promise */

text.match(/{{.*?}}/g).map(function(template) {

return getTemplate(template.match(/[^{].*[^}]/)[0]);

})

)

);

})

.then(function(templates) {

/* Replace the #time placeholder with the current timestamp, to check when

the request was made. */

var content = templates[0].replace(/#time/, new Date().toString());

/* For each partial, replace the placeholder inside the original text

with the full partial HTML */

templates.splice(1).forEach(function(template) {

content = content.replace("{{" + template.path + "}}", template.body);

});

/* Finally, return the processed HTML content to the browser to be

rendered. Make sure to set the correct content type. */

return new Response(content, {

headers: {

"content-type": "text/html"

}

});

});

event.respondWith(mainPromise);

});That’s one big chunk of code. To start off, the fetch event must resolve

to either a Request object or a promise of one. In our case, it’s a promise

of a request.

The event.request.url property holds the original URL of the resource being requested (in our case, one of the three pages we defined earlier). We will use this property

to fetch the original resource using the Fetch API, and after the content is

fully downloaded by the browser, we can start processing it.

The processing starts by searching for all matches of the /{{.*?}}/g regex,

which returns the placeholders and partial URL’s to be injected. With this list,

we can fetch the HTML content of our partials from IndexDB which will get passed

to the final method.

The final step involves replacing the #time field with the current timestamp,

and replacing the partial placeholders with the full HTML. With this final

processing done, it’s time to return the content to the browser so it can be

displayed to the user. Make sure to set the correct content type of the processed

text so it can be rendered correctly.

The Response object receives a plain string as a parameter (which represent the body of the

request), and an option object, which, in our case, contains the headers to be

sent to the browser for processing.

And that’s about it for the code. Nothing fancy, but it works… sort of. So let’s see it in action.

Results

Fire a python server (python -m http.server) and open one our three

pages. The first time you open any of them, you should see something similar

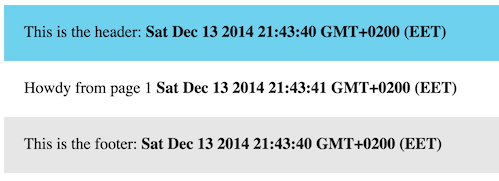

to this:

And it actually works! (Like I had any doubts, pst). The body is what we requested from the server, but the headers and footers are injected by our service workers from a cached version stored inside IndexDB.

But notice that the header, body and footer all have the same timestamp, indicating that they were all requested at roughly the same time. Now, let’s see what happens when we refresh the page:

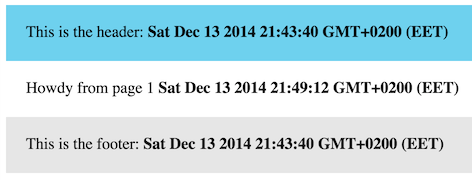

The footer and header timestamps have remained the same (21:43:40) but the

bodys has changed to now be 21:49:12. This indicates that the only the

body was requested, achieving the effect we initially planned for.

Final Words

It’s important to note that HTML pages are obviously not the only type of resource which can be intercepted and modified by a Service Worker. It works on JavaScript files, CSS and many others, opening the road to modularity in a vast ranges of files. You can, for example, cache JQuery or similar libraries which are used on all of your pages, so the browser only has to request the specific libraries used on a single page.

But not everything is rainbows. This specific method of doing content injects has a serious performance hit. The browser can no longer stream HTML content as it has to wait for the Service Worker to finish downloading the entire content. This means resources such as images or stylesheets can’t start their request until the entire original page finishes downloading. Considering this, in most cases it should be faster to just download the ATF content and then stream the rest of your page with Ajax requests.

Despite this limitation, it’s still a good technique to have in your bag, and it shows how far web technologies have come since even 5 years ago.